Not long ago, Wired magazine referred to the elusive goal of a “paperless office” as a “30-year-old pipe dream”. But tell that to the Times Review Media Group in Mattituck, Long Island, where the bins and shelving that was previously used to help organize a traditional, paper-based production workflow system were recently set aside for recycling. Within a few short months, the chain of three weekly newspapers and assorted niche magazines achieved the initiative of “going paperless” – a mission set by its owner, embraced by his staff, and fulfilled through a partnership with Software Consulting Services, LLC (SCS), which provided the software and technical expertise to accomplish the feat.

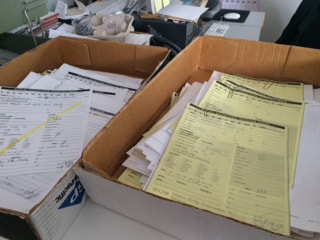

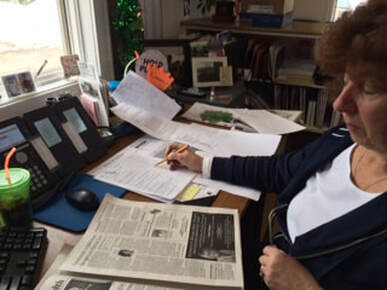

Olsen described a workflow that included a four-part form filled out by sales reps to schedule an ad in one or more of the group’s print and online products. A display ad coordinator, serving as gatekeeper, would enter all the data into AdMAX and “it would digitally flow through to the art department so that [the artists] could see that they had an ad coming for a particular customer.” There was a natural bottleneck in this procedure, however, in that work building the ad couldn’t begin till the display ad coordinator “physically brought over the carbon copy [ad order form] and the [ad] copy” and placed the paperwork into one of “a series of wire baskets” used by graphic artists to prioritize fulfillment. Only then could the ad follow the subsequent stages – proofing, customer approval, and finalization. “We did that for literally hundreds of ads every single week. That’s how we worked,” Olsen said, pointing out that “all this [was] being done on deadline cycles,” so a lot of orders and copy coming in at once tended to restrict turnaround, and a lull in submissions would inhibit art department productivity. While he had high praise for his sales team, art department, and pagination personnel, he said, the workflow didn’t foster the kind of interdepartmental communications he considered necessary. “I really have stressed integrated management of everything we do,” he said. “It’s sort of like a floor plan of a house. You want to have an open floor plan” so that each department knows what the other is doing or may need. The traditional, paper-based workflow wasn’t providing a mechanism for that to happen. “If you’re running the art department and you see that you have a whole bunch of orders that need to be done, but you don’t have [ad copy], that’s frustrating,” Olsen said. Similarly, sales reps are focused on finalizing their outstanding ads so they can “move on to the next thing.” Delays in turnaround are what frustrate them. “That sort of linear-bound process is what’s going to restrict the growth you want,” said Jackson. “It’ll look like you might have to add more people, when in fact if you just reorganize and [go] to a centralized, digital environment, you can get a lot more time efficiency out of your [existing] staff.” “The conclusion that I came away from the meeting, back in February, was we were mimicking with a manual workflow what we could do digitally,” Olsen said. With all the key people from SCS and Mattituck in the room, the two companies immediately set about discussing a path forward for the Times Review papers to achieve a more dynamic, paperless workflow. “They ended up,” Jackson said, “in a really, really good place.”  The Path Forward The challenge for a lot of papers making a transition like this, according to Jackson and his colleagues at SCS, is that a paperless workflow is a deviation from the familiar. An ad order form and hard copy – passed around in a clear plastic ad jacket – have physical substance that sales reps and graphic artists come to rely upon in handling production workflow. The hurdle, said Jonathan Ebling, product manager for SCS/Track, is “realizing that if the paper goes away, you’re still going to be able to put ads out and do your job.” “It’s a comfort thing,” he said. “It just takes an effort from everybody. Trust[ing] the system has a lot to do with it.” Back in Mattituck, the team experimenting with the new web-based software and digital processes was limited at first to a couple of key employees, as opposed to “getting a ton of people in the room” to manage a wholesale transition. “It’s good to get some specialists,” Olsen explained, “and as the specialists gain knowledge with it, and expertise, then they can help share it with everybody else.” Ebling said the leads were instrumental in raising confidence among the rest of the staff. “They showed everybody else: ‘Hey, look, I can do it, so you guys can do it, too.’” From there, it was a matter of “starting to build a comfort level – not only with the new workflow,” but also in accepting change. Even then, the scope of the transition was limited to a segment of the company’s business – not rolled out across all its products at once. “We started trying it in a very small, controlled way,” Olsen said. “We did it with our magazine business [first],” holding off until later any workflow changes affecting the company’s three community newspapers. “You have to be very calibrated with how you do it, and you have to be very deliberate,” Olsen said. “It’s not like just flipping a switch and it happens. You really have to work at it. You have to set it as an objective, as a team, and go after it, and know that it can’t just happen in two days. In our case, it took several months to get to the point where we are now.” On the sales side, Olsen said, there was “a little bit of a learning curve, but we had a couple sales reps that had a high aptitude to do it.” They started entering orders digitally on a laptop or tablet while at home or on the road – “wherever they had an internet connection.” Jackson noted that once the sales reps are unbound from the office – able not only to place orders but also to access customer information without returning to work – the dynamics of their workflow change. Most notably, the ritual practice of turning in a stack of paper tickets and ad copy – on deadline – is disrupted. Instead, an individual order is taken and entered into the system as soon as the customer commits to an ad. Ad copy is also transmitted electronically – including logos, art and layout instructions – and routed “right into the ad tracking department and the ad building department for those folks to start working on it,” Jackson said. Any delays associated with ad reps having to return to the office to submit a paper ticket or ad copy are eliminated. “All of the deliverables that used to be foot-soldiered all over the place – those are gone,” Jackson said. That includes the intermediate proofing steps necessary for customer approval and finalization, since the system also features digital markup tools with which artists can interact with sales reps and advertising customers to facilitate the completion of the work and handle all the formalities. According to Olsen, the new process “was faster for the sales reps” and they “liked it better.” The creative team reaped immediate benefits, too. “All of a sudden, the art department could not only have the order immediately, without having to wait for the display coordinator to be able to key it in, but the ad copy was also provided as digital text. “Before,” Olsen said, “[ad reps] would just scribble it on a piece of paper, and it was very difficult in many cases to read their handwriting.” “I said to my head of production, ‘Do you like it better?’ and he said, ‘I absolutely love it!’” Olsen reported. The production employees are “just so much more efficient now that they would never want to go back to the old way of doing it.” The Justification One of the more persuasive arguments for the investment in a paperless workflow solution, Jackson and Ebling agreed, is what Jackson called “the higher level business case” that “salespeople can be more efficient out in the field by using this tool.” “It frees up time for sales reps, in particular, to be selling,” Ebling said. “That’s what they really need to be doing.” But Jackson said there was also convincing evidence that the investment can be recouped simply by minimizing the incidence of error that is endemic to a traditional, paper-based workflow. “We typically, when we put in the [SCS/Track] system, see a reduction of make-goods by about 80-85%,” he said. “If you take that number alone, in some papers, it pays for itself.” While any improvement in productivity can enable cost cutting and staff reduction, that’s not what Jackson said he sees driving papers to go paperless, especially at small papers. “They may already feel that they’re at the lowest number of FTE count that they can get to.” Olsen, for his part, plans to continue in his efforts to digitize his company’s workflow processes. His next steps include implementing SCS’s electronic tearsheet and billing solutions, and although he acknowledged these moves could save “probably a couple days of time [each week] for an administrative position,” the intent is not to cut staff, but to “use that position to help grow our business.” “Andrew is smart,” Jackson said. “He really is into automating and moving forward efficiencies for his people. He doesn’t want to cut anybody. He wants to give them more time to sell – which of course at the end of the day, is the name of the game.” Strategic Partners

Olsen expressed gratification with the transformation his company has undergone this year, so far. “I’m really happy with how much we’ve been able to accomplish in a relatively short amount of time,” he said. “In basically a half a year, we were able to get the entire workflow revamped to be a paperless, digital workflow.” He gave a lot of the credit to SCS. “I’m so happy that we’re working with [SCS] as a partner and that we’re working together strategically,” he said. “I think that’s really key.” |

SCS Team

Articles in the SCS Blog are written by SCS employees and associated news outlets. Archives

June 2021

Categories

�

|

|

Software Consulting Services, LLC

252 Brodhead Road, Suite 400 Bethlehem, PA 18017 |

Our Privacy Policy

Copyright 2024 Software Consulting Services, LLC

Copyright 2024 Software Consulting Services, LLC